What is the value of persistence in an innovation process? A discussion with Millennium Technology Prize winner Robert Langer and applied psychology researcher Elisabet Lahti

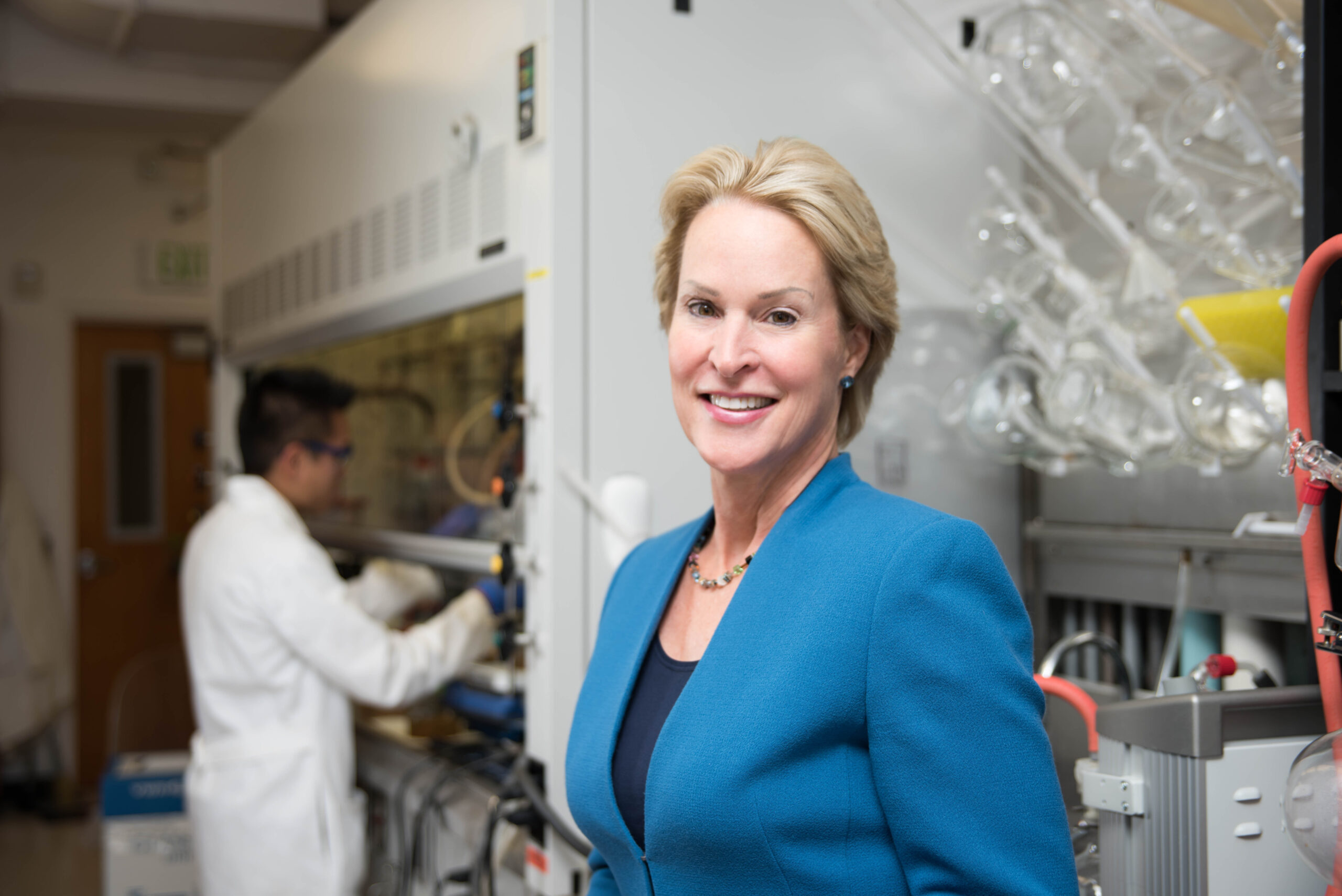

Robert Langer, winner of the Millennium Technology Prize 2008 and Elisabet Lahti, researcher of sisu

Innovation is not solely about groundbreaking ideas; it’s about the perseverance and determination to push boundaries even when faced with challenges. We interviewed Millennium Technology Prize winner Robert Langer and applied psychology researcher Elisabet Lahti to understand what it takes to succeed in the long game of impactful innovation.

When Robert Langer was starting his work in the 1970s on what would later lead to mRNA-based medicines, his first nine research grant applications were rejected. The idea of a chemical engineer studying medicine delivery via nanoparticles sounded too ambitious. Funders didn’t believe the idea was feasible.

“Successful people are often those who deal well with failure.”

Robert Langer, Millennium Technology Prize 2008

Without any success with his research grant applications, Langer pursued academic positions where he could advance his research – but he struggled to find a job. Again, his research interests were considered foolish and unrealistic.

“Those must have been the four to five hardest years of my career,” Langer admits.

Langer is not the first scientist whose ideas have been rejected. In Europe alone, success rates for funding calls vary from 8% to 21%. This means up to 92% of applications are rejected. Being a researcher with an idea is a demanding career choice. Yet, some researchers, like Langer, press on and navigate their way to success.

“Successful people are often those who deal well with failure,” says Langer. He sees failure as an essential part of the scientific process. Trial and error belong in the job description. This in itself creates perseverance – a key trait for any innovator.

Langer is now known primarily for his innovations in drug delivery and biotechnology. His research in mRNA delivery played a crucial role in developing Covid-19 vaccines. mRNA technology also has great potential for treating other health conditions such as cancer, rare genetic disorders and infectious diseases. Langer has received over 200 major awards, including the Millennium Technology Prize, has published over 1,500 research articles and holds over 1,000 patents worldwide. He is thought to be the most cited engineer in history.

Yet, if he had listened to the sceptics in the 1970s, this work still wouldn’t have come to fruition.

“Prizes such as the Millennium Technology Prize enable us to discover the stories of those who have accomplished what we aspire to achieve, allowing us to learn from and be inspired by them.”

Robert Langer, Millennium Technology Prize 2008

Persisting through rejection requires grit and sisu – the Finnish superpower

Successful innovators are defined by their ability to stay in the game long enough to realise their goals. This persistence stems from personal traits such as grit and sisu – concepts that have recently received increasing research interest in psychology.

The term “grit” has been made known by Professor Angela Duckworth at the University of Pennsylvania. She describes it as “passion and perseverance for long-term goals”. Grit embodies a person’s dedication to an ambitious goal, even in the face of scepticism from others.

Sisu is a trait that helps an innovator push through what might feel impossible – or years of rejections or setbacks, as in Langer’s case – so that they can see their work through. Elisabet Lahti, the pioneering researcher of sisu and a former student of Angela Duckworth, describes it as “extraordinary determination in the face of adversity and the ability to take action against all odds”.

Sisu has its roots in Finnish folklore and has historically been used to describe Finland’s miraculous opposition to the immense Red Army of the Soviet Union during the Winter War of 1939–1940.

“Sisu begins where perseverance ends,” Lahti explains.

Her interest in researching sisu arose from her curiosity about how some people survive extreme adversities. “It describes the embodied fortitude we can find within ourselves when we think we’ve used up all our resources.”

Lahti opines that sisu is especially relevant today, as humankind is facing a multitude of complex struggles. “Sisu is a spare tank of deep inner fortitude that can come to the fore when times get tough.”

Collective resilience can be even more valuable than individual success

Lahti’s research is focused on understanding how to promote sisu in individuals and communities and how leaders can make use of it. She argues that by understanding what kinds of conditions sisu thrives in, we can shape and construct our existing communities and societies to better serve this quality.

“How can we support each other in solving global challenges instead of persisting through obstacles in isolation?”

Elisabeth Lahti, researcher of sisu

Sisu can be a positive force to drive healthy resilience and action, but it can also be misconstrued as a misguided form of motivation. Lahti has researched sisu in the context of working life and learned that it can also become a negative cultural trait. Sometimes, sisu is used to compel individuals to endure unreasonable expectations – a way to urge people to “just suck it up”. This can erode psychological safety and hinder creativity in the working environment.

“It is crucial to realise that constructive sisu is a call to cultivate balance between being tough and supple,” Lahti explains. She also notes that sisu can be collective. It’s not solely about discovering personal resilience; it’s also about fostering it collaboratively. Lahti asks, “How can we support each other in solving global challenges instead of persisting through obstacles in isolation?”

“Listen to the feedback even if you don’t agree with it.”

Robert Langer, Millennium Technology Prize 2008

Langer emphasises the significance of both teammates and colleagues, recognizing their support and belief in his research pursuits, especially when official recognition was lacking. He also believes role models are important.

“Prizes such as the Millennium Technology Prize enable us to discover the stories of those who have accomplished what we aspire to achieve, allowing us to learn from and be inspired by them.”

With the help of his support network, Langer kept working toward his goal, publishing papers on his successes and applying for grants. “We could see the results with our own eyes. We knew that our ideas were conceivable,” he says. While he waited for the right funding, Langer spent his time delving into various aspects of biotechnology with the help of other funding he received, making him a well-rounded expert in his field.

When Langer received his first grant for studying macromolecules, such as mRNA, in 1980, he could see that all his hard work was starting to pay off. Undeniably, the diverse pathways and detours Langer had taken along the way were pivotal in shaping the success he enjoys today.

Langer’s advice to younger scholars facing rejection is simple: “Don’t give up easily and keep trying. Listen to the feedback even if you don’t agree with it. Focus on work that will be impactful – not incremental. Take risks. Failure is okay.”

How to ignite your inner sisu:

Elisabet Lahti’s three tips

- Embrace even those challenges that feel daunting or impossible. By predisposing yourself to situations that require you to push beyond your usual abilities and comfort zone, you teach your brain to be comfortable with some discomfort.

- Prepare for challenges before they arise. Envision the various hurdles you might encounter on your journey and pre-plan strategies for navigating them. This approach, favoured by professional athletes, proves effective for leaders and innovators alike.

- Practice being open to real connection. True bravery lies in keeping your heart open and allowing yourself to be vulnerable in the presence of others. These encounters help us forge robust connections with others – connections that can carry and support us through challenging times.